what I read last week

piranesi, the motherload

Good evening!

This past week, I read the magical realist novel Piranesi, which I’ve wanted to read since it won the Women’s Prize for Fiction a few years ago, and Sarah Hoover’s memoir, which was just published a few weeks ago. I also read Onyx Storm, the third installment in Rebecca Yarros’s bestselling fantasy series, but honestly, I hated it so much that I won’t be discussing it in this Substack.

Let’s get into it.

What I read:

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

Piranesi is a work of magical realism that takes place in a fantastical House comprised of endless marble halls. The House is “no ordinary building: its rooms are infinite, its corridors endless, its walls are lined with thousands upon thousands of statues, each one different from all the others. Within the labyrinth of halls an ocean is imprisoned; waves thunder up staircases, rooms are flooded in an instant.”

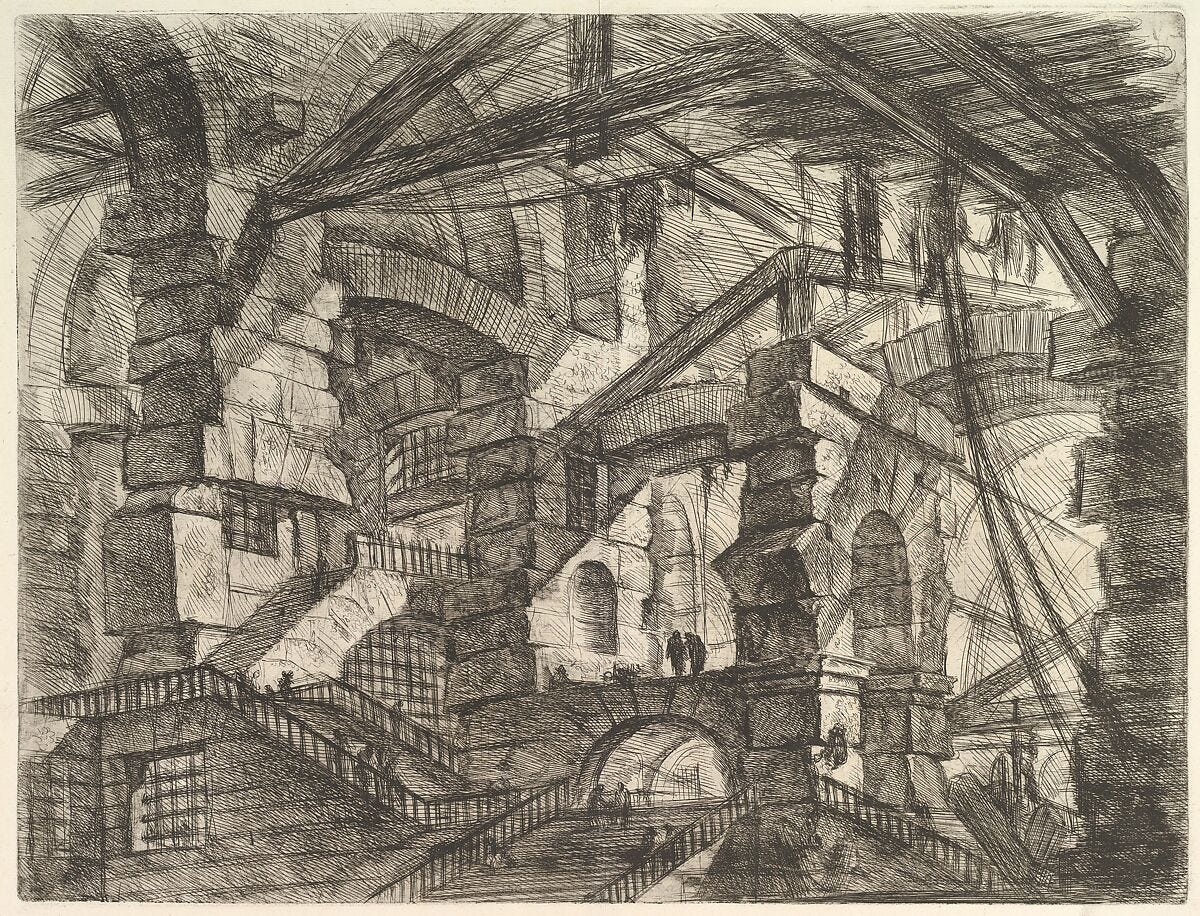

Two people live in this House: Piranesi and a man called The Other. This epistolary novel is written as a series of Piranesi’s journal entries. Piranesi spends his days exploring the House, tending the bones of the dead, and trying to survive (he fishes on the bottom floors, teaming with sea creatures and waves; mends his clothing; dries seaweed for fires, etc.). Piranesi has no memory of being anywhere else and does not even know his real name. The Other has nicknamed him Piranesi, which he does not seem to understand (Piranesi was an 18th-century Italian architect famous for his drawings of imaginary labyrinth-like prisons).

Twice a week, The Other visits Piranesi to discuss their research into A Great and Secret Knowledge. The Other believes the Knowledge will help “vanquish death” or perhaps give one the powers of telepathy, flight, or “snuffing out and reigniting the Sun and Stars.” Clarke follows Piranesi as he gradually uncovers the mysteries of the House and his identity.

Opinion: Many people will likely not like this peculiar and slow book—Piranesi spends a lot of time admiring marble statues, gathering seaweed, and speaking to birds. However, it’s also spellbinding, surprising, and ultimately uplifting. A lot is going on in this quiet novel. We have a magical missing persons case (Who is Piranesi?) wrapped in several mysteries (Why is he there? Who is The Other? What is the Great and Secret Knowledge?) wrapped in an enigma (What is the House?).

My favorite aspects of Piranesi are the allegories and intricate symbolism. Clarke draws on famous labyrinths and escapist worlds in literature, such as C.S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew, short stories by Jorge Luis Borges, the myth of the Minotaur in King Minos’s labyrinth, and Romanticism. There are also elements of Faust, the Bible, Renaissance memory places, and Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. While I enjoyed peeling back these layers, I don’t think this book needs to be read this way. Piranesi ultimately explores how we define our world and find meaning in our lives. However, since I can’t help myself, I wrote (in a spoiler-y manner) my thoughts on some of the literary references in this footnote.1

I recommend this book to someone who likes surrealistic literary fiction, but it is not for everyone!

Rating: 4.6/5

Genre: Fiction (Magical Realism)

Notable prizes/book clubs/lists: The Women’s Prize in Fiction (2021); Book of the Year (NYT, Guardian, Daily Telegraph, Financial Times, Time Magazine, Times Literary Supplement)

Page count: 272 pages

Audio: 6 hours 58 minutes

Movie/TV pairings: Pan’s Labyrinth; Narnia

The Motherload: Episodes from the Brink of Motherhood by Sarah Hoover

The Motherload is a memoir by Sarah Hoover that focuses on her struggle with postpartum depression and her relationship with her husband. The novel opens with Hoover staying at a bungalow at Chateau Marmot with her baby and live-in nanny. When her husband arrives, they get in a fight. She’s clearly struggling with depression and early motherhood.

Hoover then takes us back to her experience living in New York in her early 20s while working at the Gagosian Gallery. This part of the memoir reads a bit like Carrie Bradshaw wrote it. Hoover goes to wild art parties and meets interesting people, including the artist Tom Sachs, who is 18 years her senior. She and Sachs fall in love and get married. They build a life together but also struggle with unspoken problems and resentment. He prioritizes work over her and sends flirty texts to his ex-girlfriends. She constantly goes through his phone and does not voice her insecurities.

Hoover, who writes that she never really wanted kids, eventually gets pregnant. She seems in denial about her pregnancy. She attends the requisite doctor appointments but does not attend any birthing classes or do her own research. She’s also struggling to process her sister’s pregnancy (her sister’s baby was stillborn). Hoover recounts her pregnancy, birth, and the first year of her child’s life as she struggles with postpartum depression.

Opinion: Motherhood can be isolating and dissociative, and Hoover is very vulnerable and honest about her postpartum struggles in this book. She’s also a decent writer and writes descriptively about her relationships and environment.

However, I found Hoover’s privilege and wealth incredibly distracting and unrelatable. I do not mean to suggest that the wealthy do not experience trauma or depression. However, as one reviewer pointed out, “There’s zero interrogation . . . about her lifestyle to the point that you’ll be hearing all about her depression, but you’ll also know what she was wearing in that moment.”

For instance, Hoover describes her husband being overwhelmed at the first doctor’s appointment during her pregnancy. When the doctor informs them that they won’t be able to travel after July, he starts weeping and asks: “So you’re saying if we wanted to go to Spain in August, we couldn’t go?”

Later, when her water breaks, Hoover argues with her doctor about when she should go to the hospital. She wants to get her hair highlighted at Bergdorf’s before the birth. The doctor has to convince her that it is medically necessary for her to go to the hospital. They compromise, and Hoover gets a blowout across the street from the hospital instead.

After her child is born, she has a live-in baby nurse and forces herself to spend 30 minutes each day playing with her child. There are no sleepless nights. At her son’s first birthday party at the Claridge’s Hotel in London, she reveals that she barely understands how to change his diaper. I’m not suggesting that spending more time with her baby would cure her postpartum depression. She needed therapy and medication. However, I found her lifestyle (and lack of awareness around it) very distracting and was sadly a bit exasperated with this book by the end of it.

Overall, I respect Hoover for being so honest about her struggles, and I think it’s important for more people to talk about postpartum depression and how early motherhood isn’t necessarily this beautiful, amazing time for women. However, I would not recommend this memoir.

Rating: 2.5/5

Genre: Nonfiction (Memoir)

Page count: 352 pages

Audio: 11 hours 31 minutes

What I generally can’t stop thinking about:

This has been a huge week, so there is a lot on my mind:

The private firefighters on call for Californians who can afford them.

Tariffs (and Justin Trudeau’s response).

For a laugh, watch this comedy bit on Instagram from Please Don’t Destroy. They imagine how the NYT newsroom comes up with the emails they send to you:

What I cooked:

A lamb + mezze feast: Lamb chops with whipped feta, halloumi salad, hummus, baba ganoush, za’atar flatbread, and tahini-glazed carrots.

SPOILERS FOR PIRANESI BELOW:

/

/

/

/

/

/

A quick recap of the plot twist: In modern London, we learn that The Other (Dr. Valentine Andrew Ketterley) was a student of the Prophet (Laurence Arne-Sayles), an anthropologist who created a ritual to open a portal to another world (the House). Arne-Sayles trapped people in the House over the years, and many of them died in the House.

Piranesi’s real name is revealed to be Matthew Rose Sorenson, a writer who was working on a book about Arne-Sayles. Sorenson interviewed Ketterley as part of his book research. During that interview, Ketterley trapped Sorenson in the House so he could learn more about the world without testing it on himself. Piranesi/Sorenson has been trapped in the House for six years and has forgotten his name because of the amnesiac qualities of this world.

“16” is Sarah Raphael, a police officer who went looking for Sorenson after a woman named Angharad Scott provided the police with a new lead on Sorenson’s missing person case. Sorenson had spoken with Scott (who wrote a book on Arne-Sayles) six years ago. She never heard from him again. This year, she called Sorenson’s college in London to see what happened with his book and learned that he had gone missing. Scott, who was aware of all of the people who had gone missing around Arne-Sayles, contacted the police, which prompted Raphael to investigate the case.

Raphael entered the House through the portal and found Piranesi/Sorenson. Ketterley dies in the flood, and Piranesi/Sorenson eventually decides to leave with Raphael. Sorenson, Raphael, and James Ritter (who also had been imprisoned in the House at some point before Piranesi/Sorenson) periodically visit the House from the real world.

Themes, allegories, literary references, etc.: There is a lot going on here, and all of these ideas tend to overlap. There are Biblical elements in C.S. Lewis’s work. Romanticism influenced Borges. Plato influenced Coleridge. One could probably write a literary paper on any of these ideas, but I will only touch on them briefly below.

C.S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew: One of the two epigraphs in Piranesi is a quote from the villain in The Magician’s Nephew: “I am the great scholar, the magician, the adept, who is doing the experiment. Of course I need subjects to do it on.”

The Magician’s Nephew is set in Lewis’s Narnia multiverse. Uncle Andrew Ketterley tricks his nephew and his nephew’s friend into going through a portal into another world. Ketterley uses the children as test subjects.

The parallels between Piranesi and this story are clear—The Other even shares the same last name (Ketterley) as the uncle. Clarke also weaves in other Narnia references throughout Piranesi. For instance, Piranesi/Sorenson’s favorite statue is of a faun holding his finger to his lips (resembling Mr. Tumnus). He also dreams of a girl meeting a faun in the snow (Lucy meeting Tumnus).

The Bible: Narnia is a Biblical allegory, and Piranesi also has religious references. Sarah Raphael has the same name as the archangel Raphael (the angel of healing). The House also reminds me of a type of Eden, which Piranesi/Sorenson is kicked out of (although, in the end, he can still visit the House even after he leaves). The floods at the end of the novel also echo the Biblical floods.

Jorge Luis Borges (+ Piranesi + Minotaur): Borges wrote several short stories on labyrinths. He was influenced by Piranesi’s sketches (he even had Piranesi prints in his office) and Thomas de Quincey’s Romantic interpretation of Piranesi’s sketches. For de Quincey, Piranesi’s architecture became dreamscapes and palaces, not prisons.

The influence of Borges’s “The House of Asterion” is evident in Piranesi. “The House of Asterion” retells the myth of Theseus slaying the Minotaur from the Minotaur’s perspective. The Minotaur spends his days exploring the labyrinth, which is not a palace or a prison. Borges’s language carries through to Piranesi. Like Piranesi/Sorenson, the Minotaur pretends someone else is there that he can show around. The labyrinth is his home and his entire world. In Piranesi, there are eight statues of minotaurs in the vestibule where visitors to the House first enter from the portal.

Piranesi also reads like a twist on Borges’s “Library of Babel.” In Borges’s short story, the library consists of an infinite amount of hexagonal rooms filled with bookcases. Each book has exactly 410 pages each. The library is “perfect, complete, and whole,” because it contains every possible combination of letters and punctuations. While it is an “entire” library, its composition also makes it impossible to find anything useful (or even comprehensible) since many books are not readable—they are just nonsensical permutations of letters. In the chaos of this world, it becomes overwhelming to search for any meaning, and the people in the library go mad. The universe seems unknowable.

While an infinite labyrinth can represent an unknowable universe devoid of memory, Piranesi/Sorenson is able to view the House differently. He gives meaning to everything in the House and creates context for his world, which saves him from going mad. He catalogs and observes everything in a type of memory palace.

Perspective/Romanticism: It’s also possible to read this book as a rejection of Romanticism or a meditation on the Biblical fall from paradise. Romanticism was a reaction to the Industrial Revolution and Enlightenment. The movement prized identifying with nature and escaping the issues of society through imagination and art. In Piranesi, Clarke shows us that it’s impossible to return to an enchanted world and reverse progress (like in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave). We can’t go back to paradise through Romanticism or by finding the Great and Secret Knowledge.

The Other/Ketterley and Piranesi/Sorenson have wildly different perspectives on the House. They even experience time differently. Ketterley repeatedly tells Piranesi/Sorenson: “You get days and dates wrong.”

The Other/Ketterley is a Faustian character who sees the world for his gain. The Great and Secret Knowledge is a way to “vanquish Death” or “dominate lesser intellects and bend them to our will.” However, he is also a Romantic thinker. He comes from a disenchanted society and wants to recover what has been lost: “The knowledge we seek isn’t something new. It’s old. Really old. Once upon a time people possessed it and they used it to do great things, miraculous things. . . They abandoned it for the sake of something they called progress. And it’s up to us to get it back.”

For The Other/Ketterley, the House is a means to an end (reversing disenchantment). To him, “there isn’t anything powerful [in the House.] There isn’t even anything alive. Just endless dreary rooms all the same, full of decaying figures covered with bird shit.” Ketterley sees it as a type of prison—“A vision of cosmic grandeur, I suppose. A symbol of the mingled glory and horror of existence. No one gets out alive.” He cannot see the beauty of the House and doesn’t understand it.

In the House, Piranesi/Sorenson is, in many ways, living in a premodern world before the “progress” that Ketterley alludes to. He has escaped the disenchanted world of modern London from which he came and is living out some Romantic ideal of communing with nature. He is a scientist whose practices are grounded in observation. He studies the tides and constellations and makes a calendar. He adopts ancient religious practices, like tending to the bones of the dead and making offerings to the dead. Piranesi/Sorenson views the House as more than just a resource. He reveres his world and understands it.

However, Clarke shows us that this enchanted lifestyle is ultimately an illusion. This plays out on a few different levels. First, the world of the House is not perfect. As Raphael points out, “I said that this is a perfect world. But it’s not. There are crimes here, just like everywhere else.” Piranesi/Sorenson is also in the House because Ketterley kidnapped him.

Second, Piranesi/Sorenson understands that the purpose of the world and life is not to find the Great and Secret Knowledge. As he says to Ketterley, “[T]he Search for the Knowledge has encouraged us to think of the House as if it were a sort of riddle to be unravelled, a text to be interpreted, and that if ever we discover the Knowledge, then it will be as if the Value has been wrested from the House and all that remains will be mere scenery.” To Piranesi/Sorenson, the House is “enough in and of Itself. It is not the means to an end.” He wants to continue studying the world but not as a means to obtain the Knowledge.

Searching for the Secret Knowledge can render the world meaningless in the same way that people go mad in Borges’s “Library of Babel” trying to find a book. It’s impossible to truly re-enchant the world. Piranesi/Sorenson has spent six years deriving meaning from life in other ways.

Even when he is truly “disenchanted” and grasps the full extent of Ketterley’s deception and returns to the real world, Piranesi/Sorenson still has empathy and sees the world (of the House and the real world) as a kind and beautiful place. As he says at the end of the book, “The Beauty of the House is immeasurable; its Kindness infinite.”

His reflections at the end of the book also indicate that “fall” from the House and disenchantment has made life more meaningful, not less. When describing Raphael, he writes that he initially sees her represented by a statue of a queen in a chariot—“all goodness, all gentleness, all wisdom, all motherhood.” However, he then opines that the statue that really represents her is “a figure walking forward, holding a lantern,” who is “alone, perhaps by choice or perhaps because no one else was courageous enough to follow her into the darkness.” He now can “understand her much better now . . . better than Piranesi ever could.”

After six years of solitude, other people give his life new meaning: “Perhaps that is what it is like being with other people. Perhaps even people you like and admire immensely can make you see the World in ways you would rather not. Perhaps that is what Raphael means.”