what I read last week

shuggie bain by douglas stuart, a little life by hanya yanagihara

Let me start by saying that I am, in fact, okay—though after last week’s reading lineup, that’s a legitimate question. Apparently, I thought to myself, “You know what sounds fun? Complete emotional annihilation.”

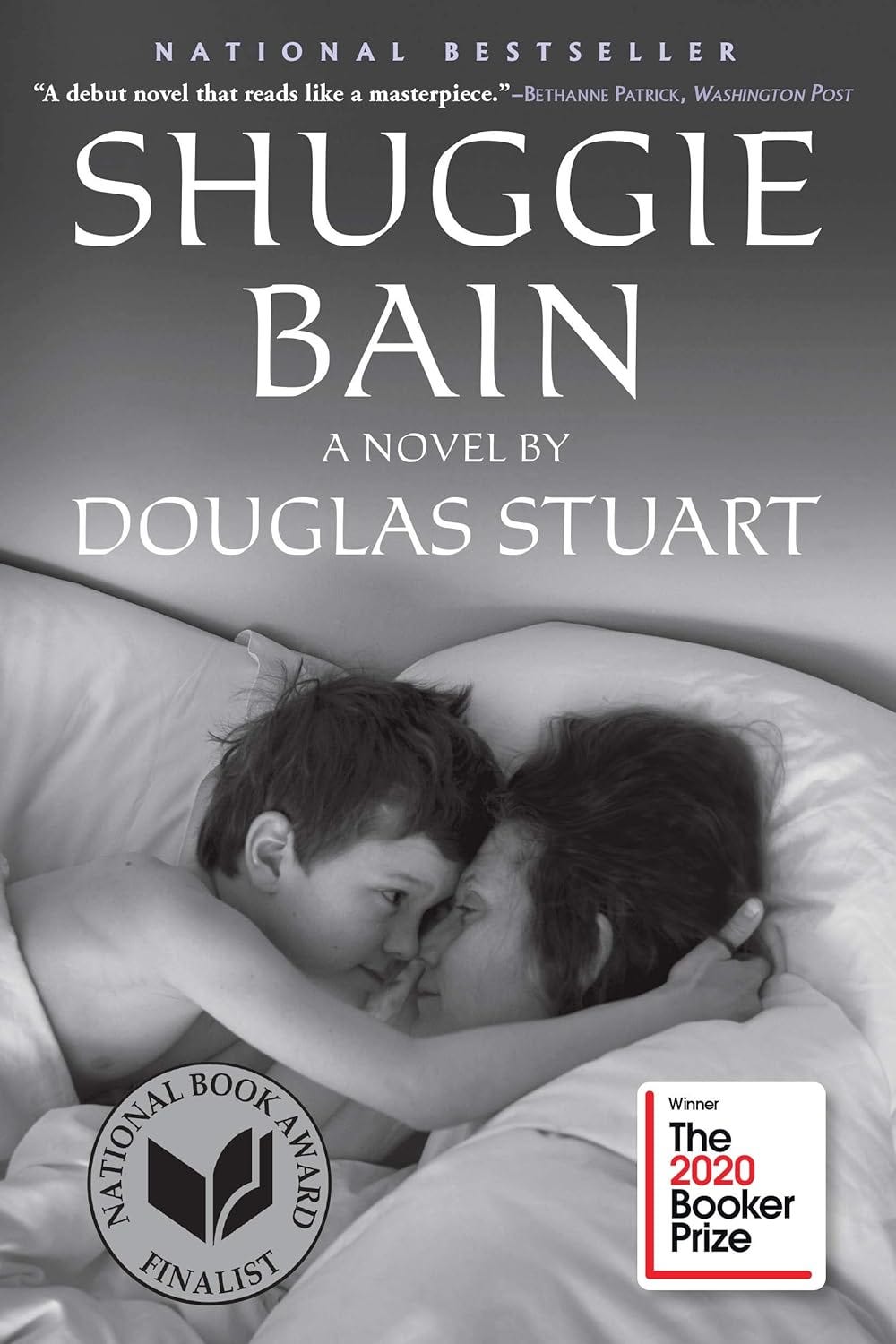

Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart tells the story of young Hugh “Shuggie” Bain growing up in 1980s Glasgow, devoted to his mother Agnes despite her destructive alcoholism. As his father abandons them and his siblings escape, Shuggie becomes his mother’s caretaker.

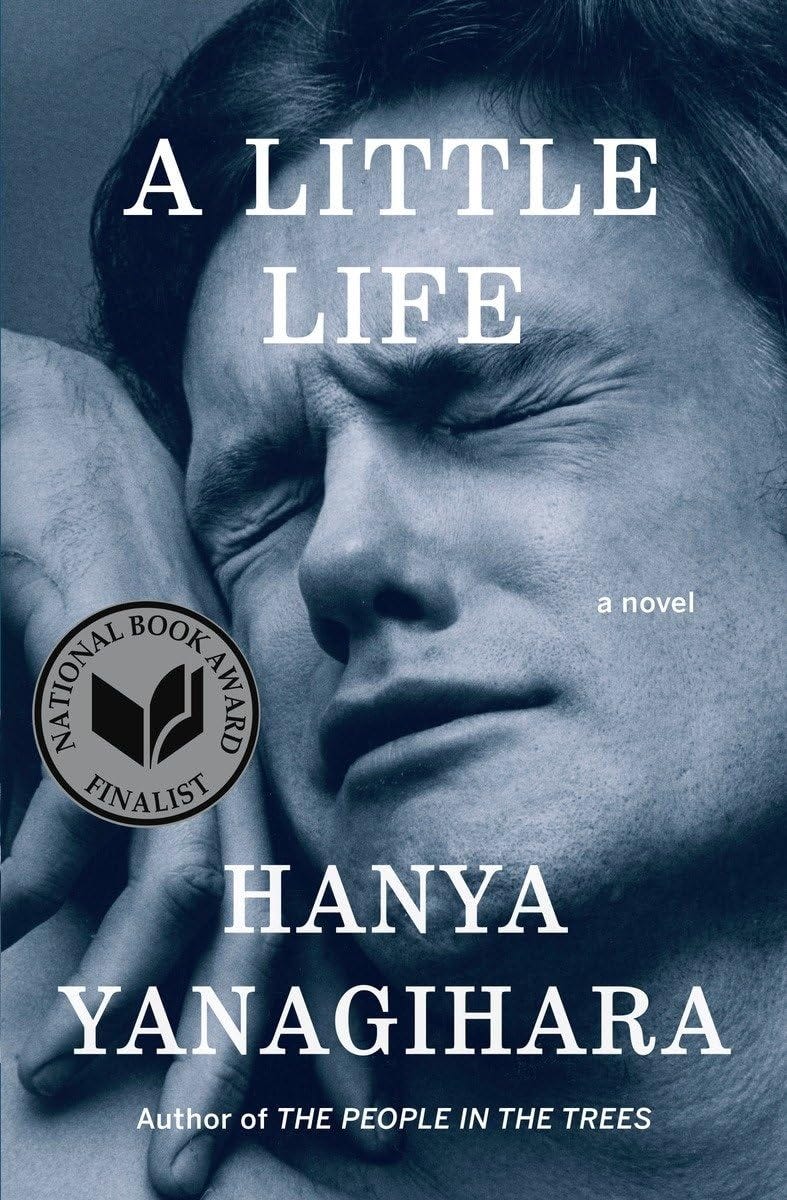

A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara follows four friends—Willem, JB, Malcolm, and Jude—from their college years through middle age, with the story gradually centering on Jude, whose mysterious past contains traumas so severe they shape not only his life but the lives of everyone who loves him.

Why did I do this to myself? I can only assume it was some twisted rejection of summer reading norms. A double dose of generational trauma and addiction is precisely what we need to close out summer, right?

I can’t say this reading experience was pleasant. But if you’re going to voluntarily traumatize yourself with literature, at least do it with books that do it well. Let’s get into it.

read📖→

Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart

Shuggie Bain focuses on a son’s complex relationship with his mother, a glamorous woman whose struggles with alcoholism define both their lives in 1980s Glasgow.

Overview: Shuggie Bain opens with a sixteen-year-old Hugh “Shuggie” Bain living alone in a boarding house and working at a deli counter. Stuart then takes us back to 1981, when Shuggie was six years old, living with his mother, grandparents, half-brother Leek, half-sister Catherine, and often absent father “Shug.”

As the youngest of three children, Shuggie becomes his mother’s primary caretaker, watching helplessly as her drinking spirals out of control and destroys their family. His father abandons them, his older siblings escape when they can, leaving Shuggie alone to navigate his mother’s addiction while also dealing with relentless bullying at school for being different—effeminate and gentle in a brutally masculine environment.

The novel follows the family as they move between different Glasgow neighborhoods. Despite Agnes’s destructive behavior, Shuggie remains devoted to her, seeing glimpses of the vibrant, loving woman she could be when sober. Their relationship is simultaneously tender and toxic. Shuggie loves his mother deeply but also struggles with the impossible burden placed on a child trying to save an adult.

Opinion: Shuggie Bain was Douglas Stuart’s first novel, and it won the Booker Prize in 2020. Stuart has since written another bestseller, Young Mungo. I put off reading Shuggie Bain when it came out, in part because a dark novel just wasn’t what I needed during COVID. I’m so glad I finally picked it up last week, even if I feel like my heart has been ripped out.

I feel like I’ve been pointing out a lot of unremarkable prose lately. Shuggie Bain is a reminder of what exceptional writing can look like. For me, it’s always in the mundane moments that great prose stands out. Take this simple scene of Shuggie turning on the water in his boarding house to wash himself:

The shared bathroom had a mottled-glass door. He snibbed the lock and stood a moment pulling on the handle, checking it had caught. Unzipping the heavy anorak, he placed it in the corner. He turned on the hot tap to feel the water, it ran a leftover lukewarm and then sputtered twice and ran colder than the River Clyde. The icy shock of it made him put his fingers in his mouth. He took up a fifty-pence piece, turning it mournfully, and pushed it into the immersion heater and watched as the little gas flame burst to life.

Or a fire breaking out in a room:

The room turned golden. The flames climbed the synthetic curtains and started rushing towards the ceiling. Dark smoke raced up as though fleeing from the greedy fire. He would have been scared, but his mother seemed completely calm, and the room was never more beautiful, as the light cast dancing shadows on the walls and the paisley wallpaper came alive, like a thousand smoky fishes. Agnes clung to him, and together they watched all this new beauty in silence.

Subject-matter-wise, Shuggie Bain is a tender, nuanced portrait of addiction and poverty. A lesser writer might have demonized these characters or reduced their suffering into something approaching trauma porn. Here, Agnes, despite her destructive alcoholism, emerges as a quietly heroic figure. She’s flawed, but she’s someone you can’t help but root for throughout her struggles. As one reviewer aptly stated: “He shows us a lot of monstrous behavior but not a single monster—only damage.”

The book’s authenticity likely stems from its semi-autobiographical origins. Stuart spent a decade crafting Shuggie Bain while living in New York and working in fashion at Calvin Klein. While he moved to New York in his mid-twenties, he grew up in public housing in Glasgow, Scotland, and lost his mother to addiction when he was sixteen.

At its core, the book explores how trauma, addiction, and poverty can affect people. While many readers may never find themselves in Shuggie’s or Agnes’s specific situation, Stuart taps into universal experiences—the fierce love between parent and child, and perhaps most devastatingly, what it’s like to grow up with a parent struggling with addiction or mental illness. Stuart summed up the incredible burden placed on a child in such a circumstance in an interview with Dua Lipa (at 25 minutes):

I knew from about the age of four that I was never the most important person in the room. That everything that affected my mother . . . would set up everything for the day—whether we had a good day or a bad day. And what does to a kid is it means you’re always compensating, you’re always trying to give that person what you perceive they lack. So you’re trying to be funny or you’re quieter or you’re neater or you’re better at school. Or you don’t eat too much, or you eat everything in front of you—whatever you think it is. And the anxiety in that is overwhelming, because you’re always trying to manage an adult’s behavior even before you know really quite what you’re doing.

Overall: Despite all of my praise, I might hesitate to recommend this book to someone, as it’s a depressing read. But if you’re in the mood for a lot of heartbreak, I’d strongly recommend it!

Rating: 4.5/5

Genre: Literary Fiction; Historical Fiction

Notable prizes/book clubs/lists: Booker Prize Winner (2020)

Page count: 430 pages

Audio: 17 hours 30 minutes

Movie/TV pairings: Shameless

A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara

Overview: A Little Life follows four college friends—Willem, JB, Malcolm, and Jude—as they navigate their twenties and thirties in New York City, pursuing careers in acting, art, architecture, and law, respectively. What begins as a story about friendship and ambition gradually transforms into something much darker as the narrative focuses increasingly on Jude.

Jude carries with him a mysterious and horrific past that he refuses to discuss, marked by physical disabilities and psychological trauma that become impossible to hide as the years progress. Despite the fierce devotion of his friends—particularly Willem—and the care of Harold, an older professor who eventually adopts him, Jude remains trapped by his history of unimaginable abuse.

The novel spans decades, showing how the four men’s relationships evolve and deepen even as Jude’s past continues to poison his present. His friends and chosen family love him unconditionally, but their love becomes both a source of comfort and torment for someone who fundamentally believes he is unworthy of care.

Opinion: A Little Life is an immensely popular book that has divided critics. It’s also a difficult one to review.

A Little Life is undeniably well-written—Yanagihara has a genuine talent for crafting prose and character development. But the novel exists in a strange temporal vacuum that initially frustrated me. Set over several decades, it mentions no historical events—no 9/11, no financial crisis. At first, this seemed like a glaring oversight in an otherwise meticulously constructed world.

Eventually, I realized Yanagihara might be writing something closer to a Dickensian tale or Grimm’s fairy story than contemporary literary fiction. This framework arguably makes the novel’s extremes more comprehensible, if not more palatable.

I thought I had a high tolerance for dark material, but A Little Life felt like literary rubbernecking. The violence is relentless and graphic, with Jude cutting himself seemingly every fifty pages, which Yanagihara details in indulgently descriptive language—Jude’s blood is “brilliant, shimmering oil black.”

The extremes here are EXTREME. At several points, I stepped back to consider Jude’s complete life story—the litany of abuse, how he got entangled in each living situation, the implausible accumulation of trauma—it verges on the absurd. If I recounted his experiences to someone unfamiliar with the book, I think they might actually laugh (albeit uncomfortably) at the sheer implausibility of it all.

The novel becomes an endless series of ugly twists, each one darker than the last—even the title itself becomes tainted by the book’s revelations. Most of the friends I talked to who loved this book described it as “poetic” and “intense.” My primary question after finishing was: What was the point of all this suffering? Yes, it’s a moving story about friendship and a heartbreaking tale of trauma, but to what end?

Perhaps it’s unfair to do so, but I couldn’t help but compare this to Shuggie Bain. Both books contain horrific abuse, but Stuart’s novel carries an emotional truth that transcends its specific setting, while Yanagihara’s feels constructed for maximum emotional impact.

Criticisms aside, Yanagihara succeeds in keeping readers invested in this implausible world. You care deeply about these characters, even when their suffering becomes almost cartoonish in its intensity.

For me, the unrealistic parts of this novel prevented me from really connecting with the material. I’m just not in the camp of readers who find this among the greatest novels ever written, despite knowing thoughtful people who consider it exactly that.

Overall: I really can’t recommend this book to anyone, given how emotionally painful and relentless it is. But if you want to try it, just know that it’s polarizing.

Rating: 3.5/5

Genre: Literary Fiction

Notable prizes/book clubs/lists: Kirkus Prize Winner, Booker Prize Finalist (2015), National Book Award Finalist

Page count: 720 pages

Audio: 28 hours 38 minutes (narrated by the actor Matt Bomer)

consumed 🎬🎧🗞️→

I’ve been watching The Agency, which is based on the French show The Bureau.

cooked 🍳→

favorite* reads (so far) of 2025📚→

*an incredibly difficult exercise! but here they are my favorite reads of each month:

January: Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (fiction); Hero of the Empire by Candice Millard (nonfiction)

February: Piranesi by Susanna Clarke (fiction); River of the Gods by Candice Millard (nonfiction)

March: The Secret History by Donna Tartt (fiction); Patriot by Alexei Navalny (nonfiction)

April: Prophet Song by Paul Lynch (fiction); Save Me the Plums: My Gourmet Memoir by Ruth Reichl (nonfiction)

May: The Lost Daughter by Elena Ferrante, translated from Italian by Ann Goldstein (fiction) Just Kids by Patti Smith (nonfiction)

June: Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico, translated from Italian by Sophie Hughes (fiction); Ghost Soldiers: The Epic Account of World War II’s Greatest Rescue Mission by Hampton Sides (nonfiction)

July: Moon Tiger by Penelope Lively (fiction); Emperor of Rome: Ruling the Ancient Roman World by Mary Beard (nonfiction)

Just call me the chicken shredder